Glorious, Terrible Bar Food

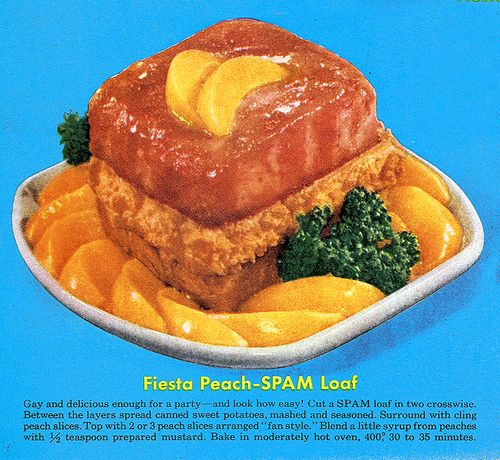

We live in troubled times, and it is fashionable to believe things are getting worse. The evidence for this view is scant, while the other side of the ledger holds reams. A more erudite refutation would draw on sociological, medical, and technological data, but I offer you: bar food. Everything about that phrase explicit and implied has improved. Bars are better; they're airier, welcoming to women, suffused with (relatively) fresh, unsmoky air. Food is better; not just bar food, all food. I mean, people actually expected you to think this was seductive 40 years ago:

The conjunct, bar food, is also better. I speak from experience, my memory having been jogged by an English pub delicacy Boak and Bailey describe today called "ham rolls in clingfilm," which is exactly as terrible as the description suggests. The range of ghastly things you could get at bars in the late 1980s, when I started drinking in them, was small. Bars then were black pits where people coagulated to drink heavily, smoke heavily, and amuse themselves with pool, pinball, juke boxes, or (very occasionally) flirting. Amenities were poor and provisional. Few bars had anything close to a kitchen, so "food" was whatever could be stored on a shelf and handed across the bar or, more fancily, microwaved first.

The most vivid of the foodstuffs to which I drunkenly resorted were 'lil smokies, one of those fancy items that the bartender had to microwave before serving. They were maybe two inches long and the girth of an average index finger. They were spiced to cover up what was obviously the hooves and snouts they were made from--and bone bits crunched under tooth as you gobbled. They were also stained a maraschino red, unnatural and unsettling (why would they try to make them look more vividly bloody?). Absolutely no sober person would ever get within a mile of them and, even drunk, you had to think carefully. The biggest draw was the price--ten for a buck--and eventually the best of us caved because of the price point. "But you get ten!" I had not yet studied under the eminent professor of economics, Patrick Emerson, partly because he was often my drinking partner, also under the smokies' thrall. Had I been, I would have realized that any bar that could make money selling 'lil smokies ten for a dollar was buying them at a price I didn't want to consider.

I am too old, too sober, and too far past closing down a bar to ever find myself in a position to crave 'lil smokies ever again. But somewhere the ghost of my younger self is sitting at the edge of the bar, swaying boozily, judging me. He knows what the smokies are, knows what the smokies will do to his innards by morning, but also knows that those moments in which he will succumb are numbered, and precious, and mark a sweet, full moment when life's possibilities are endless. I'll never eat another 'lil smoky again, but I wouldn't mind wanting to. As nostalgia goes, they are so rich with possibilities.