What Should a Label Communicate?

Good luck finding a list of the hops on that can of IPA you’re drinking. In 2025, breweries don’t do ingredients. This is no doubt the right call, despite what I may think, because there are so many ingredients and so many ways of using them that only a vanishingly small number of customers will bother reading them. More will be put off by the list itself, which seems to not inform so much as judge.

But how to communicate with customers? This is an age-old riddle, with different answers in different moments, none of them ever quite complete. Part of the problem is that the messages must serve at least two functions simultaneously: informing and enticing. These goals aren’t always compatible, though, so breweries have to think about compromises in both directions.

Craft Beer & Brewing’s Beer Industry Guide just landed in my inbox, and Courtney Iseman tackles this issue in “Tell Me What It Tastes Like.” It’s an industry-facing publication, so she offers hands-on examples of ways breweries can describe beer. I’d like to follow up on her work and add some context to this challenge and the ways it has changed over time—and offer some criticisms of the current, minimalist approach.

Changing Descriptions for Changing Times

In the postwar era and up through the 1970s, beer advertising was brand advertising. We had a beer monoculture, so nothing on the label had to inform. Basically all American beer was all the same style, strength, and color. The point of differentiation was the brand itself, which evoked domestic tranquil or outdoorsyness or let you tell at a glance whether it was a cheap or expensive beer. The label was a canvas for enticement, and nothing more.

When new breweries came along in the 1970s and ‘80s, they didn’t make just one kind of beer, and the kinds they made were unfamiliar to drinkers weaned on domestic lager. Now a label communicated a whole bunch of stuff: the name of the brand, the name of the beer, the style of the beer, its ABV, and, finally, whatever interpretive information the brewery needed to provide to reach their customers. That interpretive text might have been brief or extensive, but most labels contained something. For a long time, breweries included the IBUs, and many included ingredients as well, and a few mentioned processes. Sometimes labels contained little brewery bios.

In the past five-ish years or so, breweries have shifted to a more minimalist approach. Craft beer may not have a huge market share, but it does have a broad audience (most beer drinkers drink craft beer at least sometimes), and the majority of those drinkers are never going to be beer geeks. They want a quick hit that allows them to find the beer they’ll like. Increasingly this means simplifying style names (Czech dark lager instead of tmavý) and offering quick summaries of salient qualities about the beer.

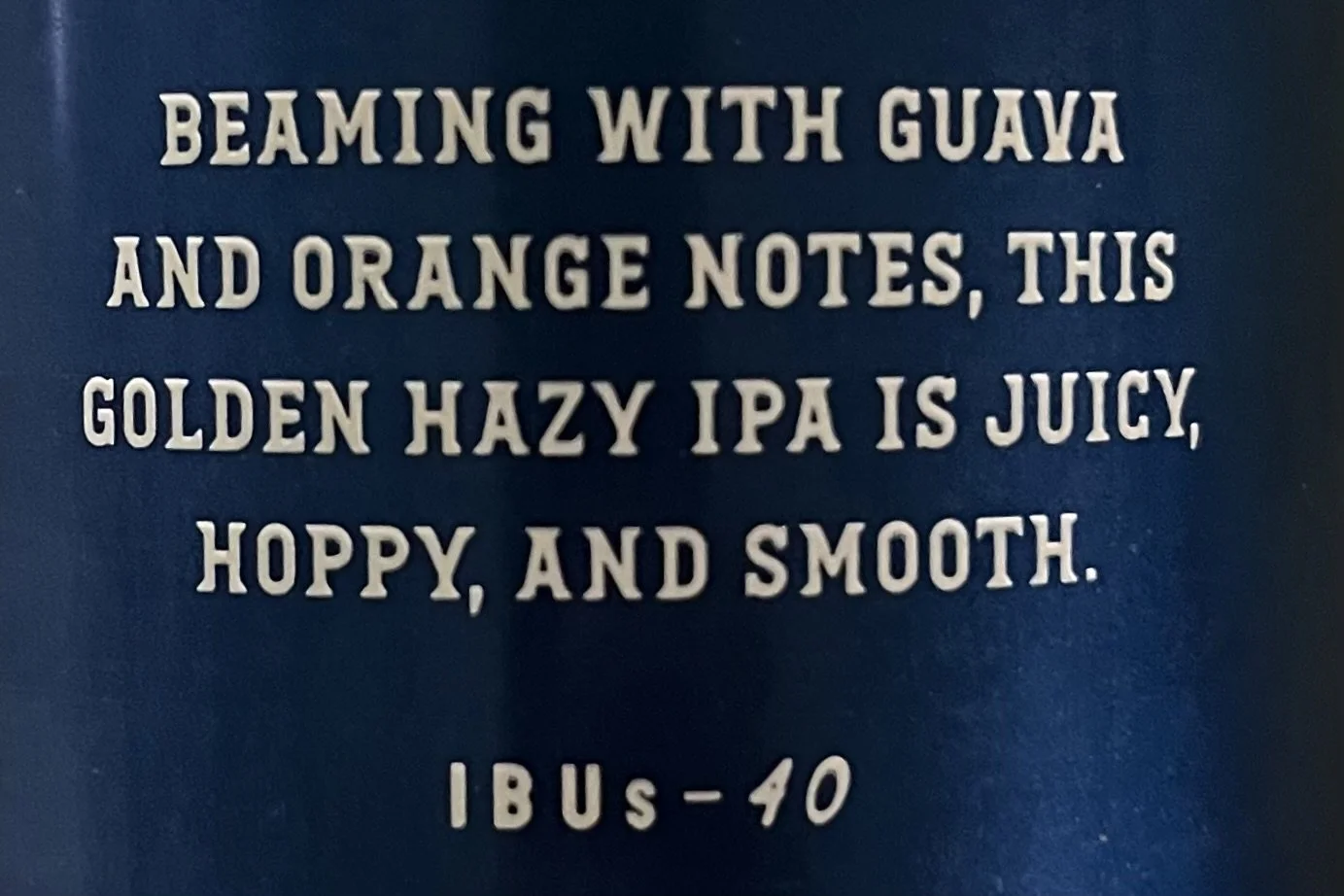

In her piece, Courtney offers the examples several breweries use: “smooth, dry, snappy” (Dovetail Pils); “dank tropical, ripe berries, and freshly zested lime” (Hop Butcher Two Thumbs Up); “papaya, passion fruit, and gooseberry” (Other Half Stacks on Stacks); “citrusy, hoppy, juicy” (Fernson Shy Giant IPA). At the top of this post, Ninkasi mentions guava and orange, and “juicy, hoppy, and smooth.” Based on my observations, these are very representative of where most of the industry is now. Three descriptions of the flavors, textures, or qualities of the beer, sometimes in as few as three words. Modern labels more often opt for a strong visual presentation that downplays text. This no doubt helps them stand out at the store—there’s the enticement—but does the brief description adequately inform them? Where’s the sweet spot?

Sparking an Emotional Connection

I think there’s a risk in going too minimal. Describing flavor is a perpetual challenge because we only have other flavors as adjectives. So we say a beer tastes like oranges or cloves or baguette. There may be a few problems with limiting a description to three adjectives, though.

When a brewery lists “citrus,” it is pointing to the flavor of hops; the “baguette” refers to the malt, and “cloves” are a specific phenolic compound that come from yeast. But for the casual drinker, beer is an often potent stew of flavors that are mainly beerlike. The flavor descriptions may actually be fairly subtle components in the overall experience—and casual drinkers aren’t going to match the adjective to the ingredient it is meant to describe. Thus these brief descriptions become background noise the drinker ignores.

Adjectives are necessarily limiting, as well. Malts are usually bready, at least to some degree, but they can often be quite distinct from one another. We don’t have a great vocabulary to describe these differences. “Citrus” is also very common, and may point to an American hop or for a European hop that is relatively citrusy relative to other European hops, but not American ones. Finally, short phrases or single adjectives, on their own, don’t have the power to entice the way a slightly longer description might, particularly when drinkers don’t match them up to their experience.

Wineries do a better job of this. The wine world generally plays much more to the lyrical, romantic impulses of their drinkers, and it turns out this not only helps them move bottles, but convinces their customers that their wines are better, too. An Australian study in 2017 looked into this effect by having drinkers evaluate wine with three differences. In one case they tasted the wines blind, in another they were given short descriptions, and in the final they received longer, more enticing ones. “Participants were 30% more likely to buy the wines with the most elaborate descriptions.” It went beyond that: “Cleverly written wine and producer descriptions can evoke more positive emotions, increasing our positive perception of the wine, our estimation of its quality and the amount we would be willing to pay for it.”

An earlier 2010 study by Cal-Poly researchers tried to assess the importance of a bottle’s back label, where wineries can include more detailed information. The results here slightly muddy the waters—only about half of the study’s 279 participants consult the back label in making a buying decision. (The most important information by far were price and wine type.) Among the group who did consult the back label, what they found there did strongly affect their purchasing decision, however.

I write about beer professionally, but I’m also a regular beer drinker. When I find an unfamiliar can of beer at the store, I study it for clues about the beer. Admittedly, I’m not the average consumer, and I get that my preference for more info places me among the minority. But I also have an experience I suspect is more universal: on those cans with too little information, I am thrown into uncertainty. It feels like more of a gamble. I more readily choose the beers I think I understand.

If I owned a brewery, I’d shoot for a happy medium and offer a sentence or two that told the potential customer a bit more about the beer. The big visuals are great, and they do seem to be the most important piece—but they are not adequate by themselves.